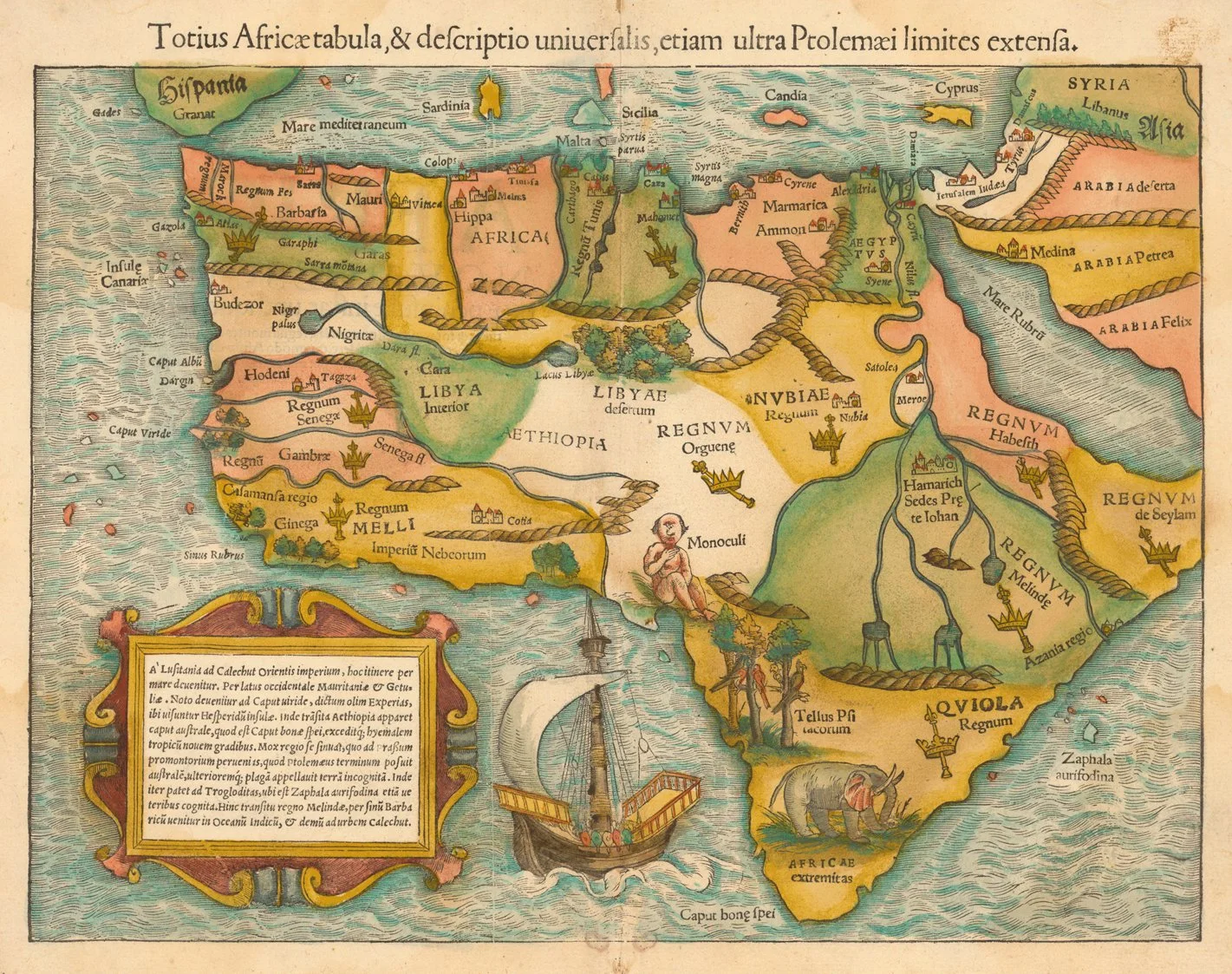

Before major diplomatic contact, Europe viewed Africans as beastly and undeveloped. A map from 1554 depicts a wildly mishappen African continent embellished with beast-like creatures, showing how little Europeans knew about Africa in the mid-sixteenth century. (Munster) Africans were viewed as strange and non-human, distinctly different from Europeans because previously, they did not have exposure to Africa. African people were considered savage and beastly for having different cultural norms than Europeans. Because they believed that Christianity was the most correct and civilized ideology, when Europeans encountered native peoples, they couldn’t accept that different cultures and religious beliefs were valid. (Alciati) Driven by ‘divine purpose’, they violently converted many and erased native culture. Stereotypes of savagery and beast-like qualities persisted into later centuries.

At that time, religion was a large factor in social norms in Europe. Europeans believed that humans were created by God in Europe, and humanity spread over time. (Zuravleff) Following that ideology, Europeans were most similar to the original image of God because they were most similar to the first humans created, and people with different features were deviations. They believed that non-European features signified sin, and the ‘strange’, ‘heathen’ culture of African native peoples seemed to prove that idea. Even as Christianity spread into Africa, the connotation of blackness representing sin and dirtiness endured. An image from an Emblem book (a collection of symbolic images accompanied by explanatory prose); white men attempt to cleanse a black man of sin. The drawing shows them trying to wash him, while the text claims this to be an ‘Impossible task’. (Alciati) Impossible because a black man’s skin cannot be washed away. He will not become white by bathing.

As contact between Europe and Africa increased throughout the mid-1500s, portrayals of Africans began to show them as civilized humans because Europeans were more exposed to Africans, somewhat normalizing them. Although it was only for Christian Africans who had been ‘saved’, artists began to represent the diversity of African features, differentiating between people from distinct regions of the continent. (Zuravleff) In Adoration of the Magi painted by Gerard David, two of the wisemen are African. (David) This is a big change from the initial idea that blackness was sin, and Africans were naturally sinful. In the painting, the Magi bear gifts for the baby Christ. They are shown in an equal position of power as the white wisemen, standing on equal ground. Unlike many other paintings, they are not servants. They also look very different from each other. One has lighter skin and a wider face, showing the painter recognized some diversity between Africans. David’s work expresses them as humans, equal to the white figures in the painting, and an integral part of the Christian story. Imagery of black saints

became more prevalent as Europeans learned more about Africa. Including Africans in Christian imagery spread the idea that Christianity was for everyone, thus expanding their realm of influence. As Christianity gained a foothold in Africa, religious institutions gained more power, and their influence grew. Faith was a strong tool used to gain control and spread political ideas when the church and state were unified.

Blackness and the Portrayal of Africans in Renaissance Art

In 1937, art conservators x-rayed a painting of the famously childless poet Vittoria Colonna. They were shocked to find a small figure who had been painted over. After extensive restoration work, a child was revealed. Many paintings like this were altered at some point to make them more profitable. After some further research, the painting was identified as Maria Salviati de’ Medici and her niece Giulia de’ Medici, daughter of Alessandro de’ Medici, duke of Florence, and one of the most prominent people of color during the Renaissance. (Blakely) We often omit people of color from European history when they were some of the most important figures. In the early fifteenth century, European fascination with the rest of the world grew. (Oxford) Although Europe and Africa had contact in earlier centuries, much of that knowledge was lost in the Middle Ages. Political leaders pushed for alleged ‘exploration’ leading to colonization, which allowed them to steal valuable resources from other continents. Europeans had preconceived notions of who Africans were, fueled by ignorance and fear of other cultures. As exposure to Africa continued, European society began opening up to people of color, and for a while, there was social mobility. At the same time, Africa became the main source of slaves worldwide, again changing the perception of blackness. Throughout the Renaissance, there were periods of change and mobility concluding in the cementation of the view of race in society. Art through these periods is a clear representation of the cultural and social norms at the time they were painted. The artistic portrayal of Africans in art changed to reflect the humanization of non-white people that came with the enlightenment of the renaissance. Prior to regular diplomatic contact, Europeans believed they were superior to Africans, attributing these differences to religion. As interaction between Europe and Africa increased, Africans were portrayed as fully human, although negative stereotypes persisted. As time went on, slavery became an exclusively black condition, reducing social mobility for people with African features. Throughout the Renaissance period, portrayals of Africans fluctuated, following cultural shifts as blackness became a defining feature.

Additionally, the normalization of blackness through holy depictions allowed further social mobility as Africans became an integral part of European society, although the perception of non-white people’s inferiority was blatant. Peter Paul Ruben’s portrait of Mulay Ahmad shows a turbaned man holding a sheathed knife in one hand, gazing into the distance. Mulay Ahmad had been the King of Tunis, but he died years before Ruben painted him. (Rubens) This portrait is an exoticized portrayal of a brutal king. In European eyes, he was an exciting champion of Christianity, spreading their ideas throughout Africa. This story is, of course, highly romanticized, and far from reality. He was seen as an exotic figure, spreading ‘pure’ ideas through far-away lands full of savagery and danger. His contemplative look illustrates him as a brooding hero, while the assured hold on his knife

shows the violence he inflicted. It is said he inspired the portrayal of African Kings in the biblical scenes. A portrait of Alessandro de’ Medici, of the powerful Italian Medici family, demonstrates an interesting duality during this period. Alessandro de Medici was the son of a freed African slave and a European nobleman. In all his portraits, he was painted with dark skin and curly hair, there weren’t attempts to hide his African ancestry. Although he was an illegitimate son, he inherited the dukedom of Florence but was assassinated by his subjects. The public believed he was vulgar and overly sexual, that he had been pursuing married women. Interestingly, these were both stereotypes associated with blackness through the idea of sin. (Britannica) It is important to recognize that African-ness was accepted only in the context of Christianity and thus, its Europeanized form.

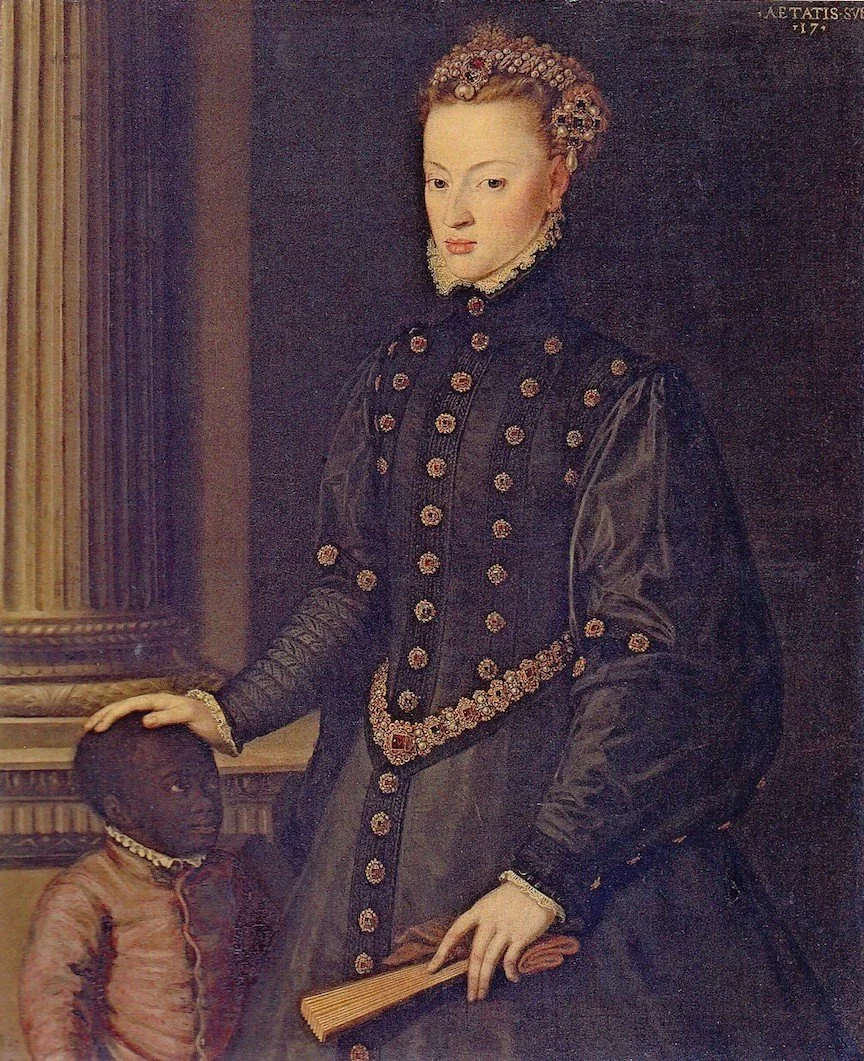

Although social mobility had increased with positive portrayals, the European perception of blackness was still subject to change. Through the late 1550s, the slave trade from Africa increased, leading to blackness being associated with slavery. (Oxford) For a long time, slavery in Europe was considered a temporary condition. Slaves were like indentured servants, and once they worked off their debt, they were free. During that time, slaves were also European, there wasn’t one race associated with servitude. From the beginning, a major export from Africa was humans. Europe needed labor after the plague killed off their workforce, and the involuntary servitude of African slaves was an economical solution. As Africa became the main source of slaves, it also became fashionable to own African slaves. (Blakely) Slavery became exclusive to Africans, changing the perception of black people’s social status solely based on how they looked. This limited the social movement of all black Europeans, even if they were free. In the portrait of Juana of Austria, a Portuguese princess, we can see her small African slave. (Moro) Notice he is dressed in fine clothing showing he is part of a rich household. He doesn’t need clothing to show he is a servant because he is black. Juana has placed her hand on his head, body language showing her ownership of him. The pose is almost endearing. He is disproportionately smaller than her, showing not only how young he is, but how much more power she has, towering over him. This returns us to the idea of whiteness being hailed as superior to all others. Even if Africans are ‘civilized’, wearing European clothes, they are not even close to equal to powerful white Europeans.

The first generation of Africans in Europe was mostly slaves, but many of their children were mixed-race or ‘mulattos’. Many of these children had opportunities to achieve higher social standing. Prominent European mixed-race figures minimized their blackness to integrate into society. Throughout Europe, laws on slavery differed. For a long time, slavery was not hereditary, so children of slaves could be free. As the nature of slavery changed, the status of a child was often determined by their father. If a child’s father was free, so was the child. (Blakely) Many second-generation African Europeans were mixed-race, so these were the children who had opportunities to gain social power. The Portrait of Maria Salviati de’ Medici and Giulia de’ Medici is a prime example. (Carucci) The Medici’s were one of the most powerful families in Renaissance Italy. (Britannica) Giulia is the daughter of Alessandro de’ Medici, the former duke of Florence. When he was assassinated, Giulia was placed in her aunt’s care. In the painting, we can see Giulia has African features, features that match portraits of her father, but her skin is painted a ghostly shade of white, matching Maria’s. The figures both look like they are carved from pale marble. Small Giulia clutches Maria’s hand, showing she is a part of Maria’s family, equal to any child of Maria’s. The painter minimized what would be Giulia’s most differentiating feature, darker skin. Painting her as white denoted her as a Medici, powerful and rich.

Unlike Juana and her African Slave, Giulia and Maria have the same skin tone, showing their equal status. Because mixed children were more European, less African, they were more socially accepted. Naturally, their skin was lighter, which would make them ‘less sinful’. They grew up in Europe, in a ‘civilized’ environment unlike amongst the ‘fantastical creatures’ in Africa, like their African parents. Social acceptance was conditional on how European ‘mulattos’ were. By emphasizing their often-noble European parentage, they fit more neatly into the European notion of white purity. Features such as skin color would always denote anyone with African Ancestry as ‘inferior’, but if those could be minimized, a person could be more acceptable. Throughout this period, European society controlled the cultural narrative of these children by pressuring them to minimize a part of their heritage.

During the renaissance period, Europe increased its interaction with other continents, and thus its knowledge about other peoples and ideas. Before consistent contact between Europe and Africa astoundingly offensive stereotypes abounded, fueled by ignorance-caused fear. As diplomatic relations strengthened, Africans were humanized, especially through religious depictions of lack Christians. With the increase of the transatlantic slave trade, prior social mobility was replaced by perceptions of blackness as a signpost of servitude. Because of European society’s distaste for blackness mixed-race figures, often children of nobility had to minimize their African heritage to achieve high social standing. Many stereotypes from this period carry into modern society, the association of blackness with sin, specifically hypersexuality, violence, and danger. Whiteness and even the color white being associated with cleanliness and purity persists. Even today, prominent people of color have had to minimize their connection to black culture to be successful and viewed as intelligent. black culture is viewed as inferior, a sign of lower intelligence. Now, history has become highly politicized, and like Giulia de’ Medici, painted over to make the portrait more palatable, we are missing important pieces that help us understand the full picture of the past. Many times, we do not acknowledge the origins of these biases and why they carry into today because we do not acknowledge the presence of Africans in Europe during the renaissance, a time of ideological exchange and social fluidity. We need to understand why modern stereotypes exist in order to combat them. It is important to recognize that the renaissance was not just a revolution of European ideas, there were many foreign influences and prominent non-white figures who pushed thinking forward.

Works Cited

Alciati, Andrea. “An Impossible Task.” Pitts Theology Library, 1492-1550, https://pitts.emory.edu/dia/image_details.cfm?ID=134370. Accessed 9 February, 2022

Blakely, Allison. “The Black Presence in Pre-20th Century Europe: A Hidden History.” The Black Presence in Pre-20th Century Europe - Blackpast, 9 July 2019, https://www.blackpast.org/global-african-history/black-presence-pre-20th-century-europe-hidden-history/. Accessed 9 February, 2022

Britannica, The Editors of Encyclopaedia. "Alessandro." Encyclopedia Britannica, 17 Jul. 2014, https://www.britannica.com/biography/Alessandro. Accessed 9 February, 2022.

Carucci, Jacopo. “Alessandro de’ Medici.” Art Institute Chicago, 1534-1535, https://www.artic.edu/artworks/110759/alessandro-de-medici. Accessed 9 February, 2022

Carucci, Jacopo. “Portrait of Maria Salviati de’ Medici and Giulia de’ Medici.” The Walters Art Museum, 1539, https://art.thewalters.org/detail/26104/portrait-of-maria-salviati-de-medici-with-giulia-de-medici/. Accessed 9 February, 2022

David, Gerard. “Adoration of the Magi.” Princeton University Art Museum, 1460-1523, https://artmuseum.princeton.edu/collections/objects/19968. Accessed 9 February, 2022

Demby, Gene. “Taking a Magnifying Glass to the Brown Faces in Medieval Art.” NPR, NPR, 13 Dec. 2013, https://www.npr.org/sections/codeswitch/2013/12/13/250184740/taking-a-magnifying-glass-to-the-brown-faces-in-medieval-art. Accessed 9 February, 2022

"European empires in Africa." Oxford Reference, HistoryWorld. Date of access 9 Feb. 2022, https://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/acref/9780191737589.timeline.0001. Accessed 9 February, 2022

Moro, Antonio. “Portrait of Juana of Austria, daughter of Charles V.” Gómez, Leticia Ruiz. “In the King’s Name | The Portrait of Juana of Austria in the Bilbao Fine Arts Museum.” Bilbao Fine Arts Museum, 1519-1576, https://www.museobilbao.com/uploads/salas_lecturas/archivo_in-19.pdf. Accessed 9 February, 2022

Munster, Sebastian. “Totius Africæ tabula, & descriptio uniuersalis, etiam ultra Ptolemæi limites extensa.” Princeton University Library, 1489-1552, https://library.princeton.edu/visual_materials/maps/websites/africa/maps-continent/continent.html. Accessed 9 February, 2022

Rosasco, Betsy J. “In Depth: Revealing the African Presence in Renaissance Europe | Princeton University Art Museum.” Princeton University, The Trustees of Princeton University, https://artmuseum.princeton.edu/story/depth-revealing-african-presence-renaissance-europe Accessed 9 February, 2022

Rubens, Peter Paul. “Mulay Ahmad.” Museum of Fine Arts Boston, 1609, https://collections.mfa.org/objects/32728. Accessed 9 February, 2022

Zuravleff, Mary Kay, et al. “Faces of the Renaissance.” The National Endowment for the Humanities, 2013, https://www.neh.gov/humanities/2013/januaryfebruary/feature/faces-the-renaissance. Accessed 9 February, 2022