THE BLACK BODY: TRAUMA & JOY

THE BLACK BODY: TRAUMA & JOY

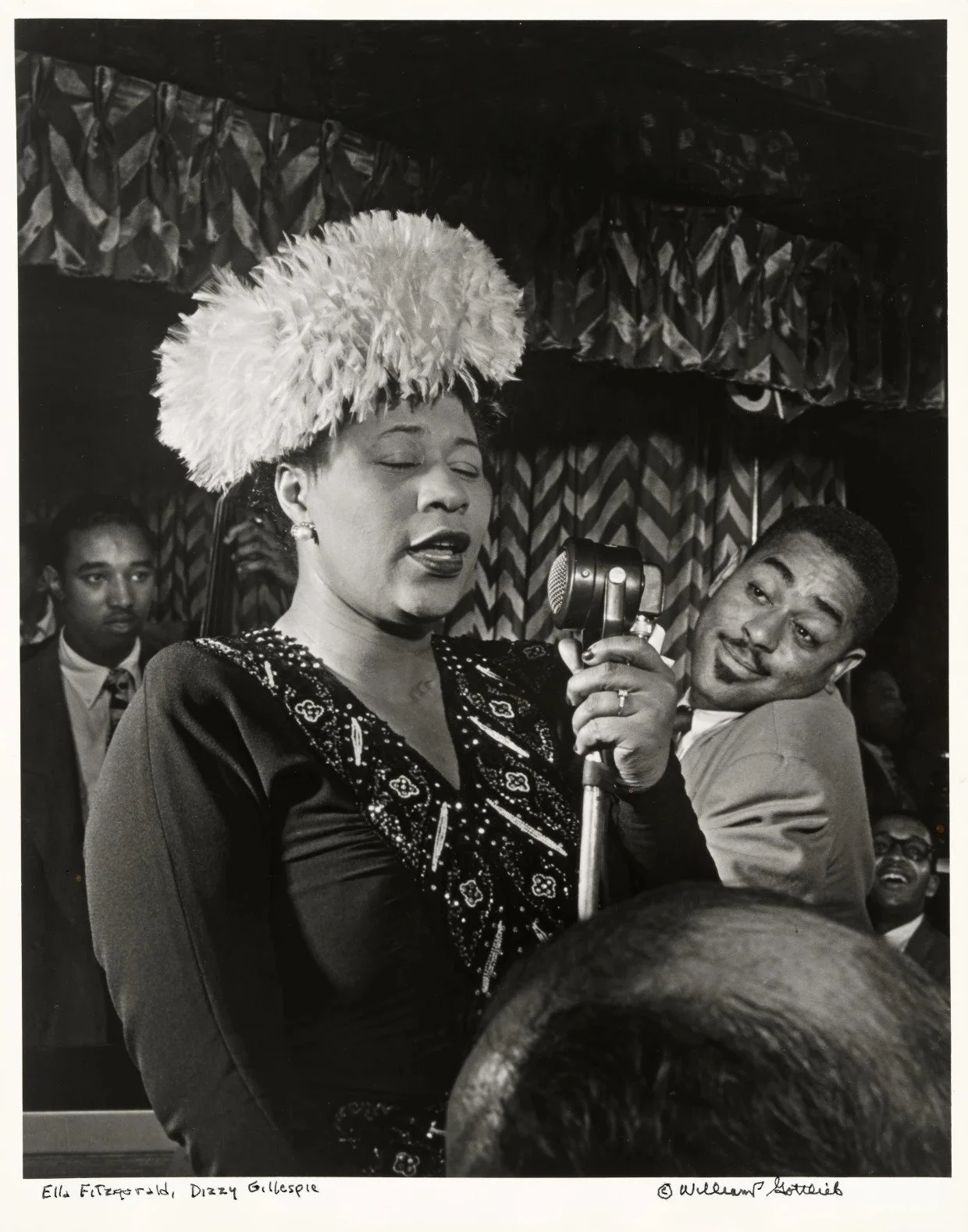

Ella Fitzgerald, Dizzy Gillespie, and Ray Brown, William Gottlieb 1947

Our bodies hold our histories. The weight of our ancestors’ pain is inescapable in the set of our shoulders, the swing of our hips, the lilt of our voices. It is through art that we become free. Beginning the Harlem Renaissance, this collection explores artists’ reclamation of the Black American experience, from generational trauma to radical joy.

Talking Skull

Meta Vaux Warrick Fuller, Bronze Sculpture, 1939

An influential creative of the Harlem Renaissance, Meta Vaux Warrick Fuller was known for exploring Afrocentric themes. In this piece, Fuller recounts an African folk tale where a man encounters a talking skull. Upon reporting his discovery to his village, the skull ceases its speech.

The central figure kneels in front of the skull, contemplating or perhaps conversing with it. Fuller contrasts his lithe figure with the lone skull. Both are stripped of their usual concealments: clothing and flesh respectively. The man’s imploring posture reflect the desire of many Harlem Renaissance artists to reconcile an ancestral African past lost through centuries of enslavement.

Sonnet to a Negro in Harlem

Helene Johnson

You are disdainful and magnificent—

Your perfect body and your pompous gait,

Your dark eyes flashing solemnly with hate,

Small wonder that you are incompetent

To imitate those whom you so despise—

Your shoulders towering high above the throng,

Your head thrown back in rich, barbaric song,

Palm trees and mangoes stretched before your eyes.

Let others toil and sweat for labor’s sake

And wring from grasping hands their meed of gold.

Why urge ahead your supercilious feet?

Scorn will efface each footprint that you make.

I love your laughter arrogant and bold.

You are too splendid for this city street.

Born and raised in Boston, Helene Johnson became known as one of the youngest poets of the Harlem Renaissance, although her career was short-lived. Published in a 1927 anthology, Sonnet to a Negro in Harlem exemplifies the cultural visibility of the Harlem Renaissance. As Black artists began to reclaim the narrative of the Black experience, they imbued African American self-identity with new power. Johnson describes the subject’s unashamed manner as they stride down the street. Radiating confidence, this individual is untroubled by DuBois’ veil of double consciousness. They know exactly who they are, and their physicality demonstrates as much.

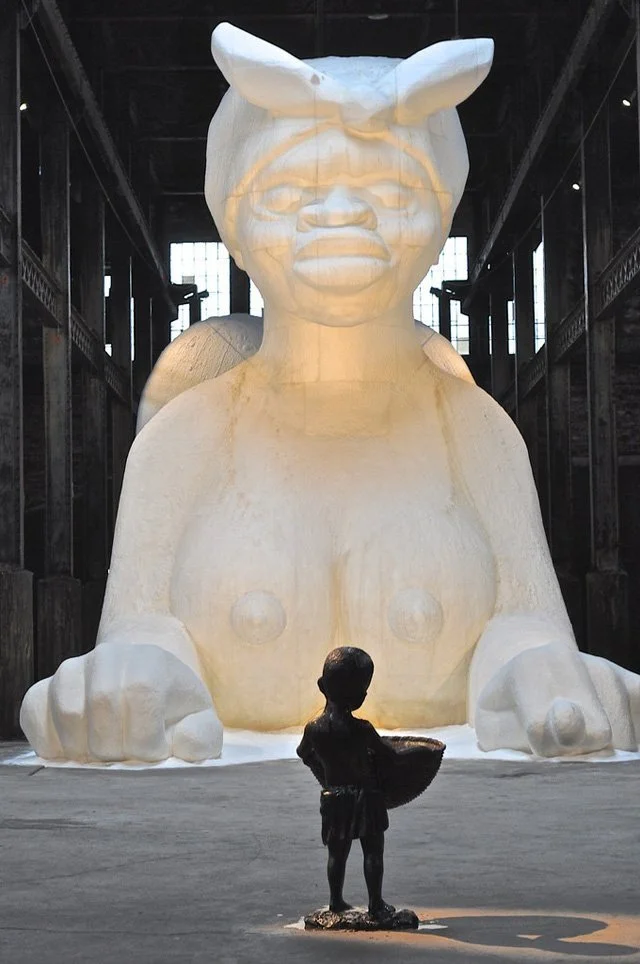

A Subtlety, or The Magnificent Sugar Baby

A Subtlety, or The Magnificent Sugar Baby

Kara Walker, Bleached White Sugar, 2014

35 feet high and 75 feet long, Walker’s sugar sphinx looms over visitors in the decommissioned Domino Sugar Factory. With unmistakably Black features and a headscarf reminiscent of the ‘Mammy’ caricature, Walker’s sculpture explores the dark history of sugar processing and its abuse of Black bodies. Walker draws inspiration from the medieval delicacies, sugar subtleties, which were consumed at grand feasts in recognition of the hosts’ power and affluence. Prostrate and nude, the sphinx becomes an indulgence to be consumed by the eyes of her audience.

The Nicholas Brothers

The 1943 film Stormy Weather shows the legendary Nicholas Brothers performing to Cab Calloway’s Jumping Jive. The Nicholas Brothers’ signature style blended tap, jazz, and acrobatics, creating routines that appeared physically impossible. They appeared everywhere from Broadway to Hollywood, reclaiming the art form that had been introduced to white audiences through minstrel shows.

Tap dance originates from the genius and resistance of enslaved people. When slave owners denied them instruments, slaves used their bodies to produce rhythms, communicating information and continuing the tradition of African percussion.

Love is The Message, The Message is Death

Arthur Jafa, 2016

Director and cinematographer Arthur Jafa presents a short film on the Black experience set to Kanye West’s Ultralight Beam. The film was synthesized from found footage whose subjects range from prominent public figures to Jafa’s personal acquaintances. Jafa utilizes what he calls “Black Visual Intonation”, a method of organizing images to create an oscillating rhythm and counter-rhythm with the music. Provoked by a wave of citizen-documented violence, Jafa combines painful clips of brutality with triumphs of Black culture, contrasting bodies twisted in pain with those writhing in exultation.